“That’s it,” says Geoff. “It looks exactly like the picture.”

I look out the window of the old commuter train, catching a glimpse of Uncle Walter’s graveyard before it is replaced by the drab Flemish countryside. Flanders looks nothing like I expected; despite our arrival at the tail end of the year, I am somehow surprised by the lack of wild poppies scattered across the landscape. We get off at the small station in Ieper (Ypres), Belgium, and are met by a rush of crisp winter air. It is grey and raining lightly; the droplets hit our toques and sensible jackets, methodically drenching us over the course of the day.

It’s a 15-minute walk to the centre of Ieper, affording the welcome opportunity to stay warm and use our legs after several hours on a train. Ypres is quaint and pretty, and it’s easy to find our way around. We arrive at the Cloth Hall, which today is an exact replica of the original 13th Century building obliterated in the War, and go inside to the tourist information desk. Geoff has a postcard to send, so I am left alone for a few minutes as he goes in search of a post box.

The In Flanders Fields Museum is housed upstairs, and tourists mill around the main floor exhibit. A German couple stands near me, talking about something in a language I can’t understand, and I start crying; the sudden well of tears catches me off-guard. I wipe the tears from my face, surprised by the surge of emotion and the juxtaposition made possible by the passing of time: here we are, Germans and Allies, less than one hundred years later, passing a rainy day in a museum housed in a building rebuilt from rubble. The pointlessness of it all – of the Great War, of Uncle Walter’s lost adolescence, of mustard gas and ancient architecture fallen by bullets and bombs – hits hard, and catches me unprepared.

Geoff returns, and the woman at the information desk calls us a cab. Along the way, we stop at a flower shop. I wait in the taxi making small talk with the driver until Geoff emerges from the shop with a dozen red roses; a gift for an unknown family member lost at an age we’ve both been fortunate enough to surpass. We pass the ride in silence, arriving 10-minutes later at the same graveyard Geoff saw from the train.

The cemetery is neat and well-kept, one of 23,000 sites cared for by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. We have the place to ourselves, and find Walter quickly using the rows and numbers assigned to each headstone and research done before the trip. VI. D. 42: a final resting place in a country an ocean from home. Seeing our surname – Matthews – etched on the headstone, we both start crying. Geoff places the flowers on Walter’s grave, we take some pictures, and I leave my husband alone with the Great Uncle he never knew. I walk towards the road, find the guestbook, and flip through comments from others who’ve made similar pilgrimages to visit their family’s dead. Most of the comments are not from sons, daughters, or grandchildren, but from nieces and nephews and their children; these men didn’t live long enough to have their own families.

***

Fast forward 11 months, and Geoff, and I are sitting around a cheap wooden table in a suite at the Delta Grande in Kelowna, BC. We are catching up with my mother-in-law, Jean, a tenacious and impressively patient genealogist. Sitting in Kelowna on the weekend before Thanksgiving, Jean is sharing with us the mountains of knowledge she’s unearthed since our trip to Great Uncle Walter’s grave near Ypres, Belgium. Geoff and I were the first of the Matthews clan to see Walter’s final resting place, and our trip unexpectedly ignited a desire in Geoff’s parents to learn more about a man who died far from home almost a century ago.

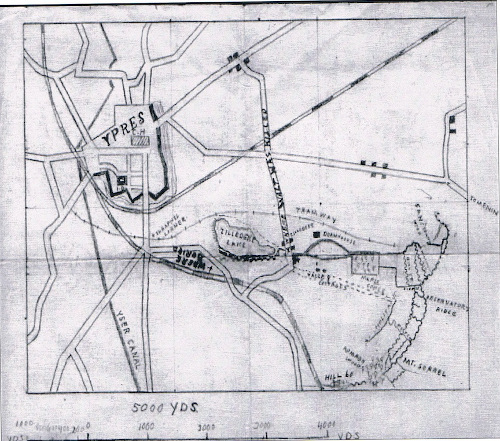

Now, 11 months after our trip and a world away, Jean is telling us the details of Walter’s life and death, an event surreptitiously recorded by Walter’s best friend on a hand-drawn map smuggled home from the war, and unexpectedly given to Jean a few months ago by a stranger-cum-friend in the Calgary International Airport.

If you look closely, you can see the words “Where Walter was killed” on the north-south road southeast of Ypres. This map is published in the book, “Second to None: The Fighting 58th Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force” by Kevin Shackelton.

Lance Sergeant Walter Franklin Matthews died on June 6th, 1916. For a long time, the family thought he’d died during Passchendaele, but, after seeing the synonymous film, Jean realized the story didn’t line up. For one thing, Walter was long dead by the time Passchendaele was fought.

After our trip to Belgium, she began the lengthy task of figuring out exactly what happened to Walter. The breakthrough came when she found the son of Walter’s best friend, David, alive in Toronto. On a brief layover in Calgary, David’s son and Jean met for the first time in the airport, and he was able to share photos, maps, and a book with the story of what happened during Walter’s final days: Walter was one of six soldiers in the 58th Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force who died on June 6 in the Battle for Mount Sorrel, or Hill 62, less than four months after arriving overseas on a ship from Montreal.

This photo is published in the book, “Second to None: The Fighting 58th Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force” by Kevin Shackelton, and the original is now in my mother-in-law’s possession, after David’s son kindly gave it to the family.

***

It’s hard to describe the feelings our visit to Walter’s grave brought up. Mostly, I felt guilty that we’d never visited the final resting places of our family members – Walter, my grandmother’s brother in Holland, and my grandfather’s brother in France — who, despite never having had the chance to know us, died that we may live. While the experience hasn’t changed my day-to-day life in anyway, it’s certainly given me a new appreciation of the sacrifices made during war, and the significance of November 11.

If You Go:

- The Commonwealth War Graves Commission runs an excellent website at which you can look up the location of individual graves using a variety of search parameters.

- The Ypres Tourist Board has an excellent website to help plan a trip

- We visited in December, and the weather was quite manageable; in addition to the tourist activities related to the world wars, Belgium has wonderful Christmas markets at that time of year, running roughly from late November to early January.

Similar Stories from Other Canadian Travel Bloggers:

- Nat & Tim from A Cook Not Mad went to visit a family member’s grave in Italy in their post, A Day of Remembrance

- Lisa Goodmurphy of Gone With Family took her kids on a D-Day Tour of Normandy

- Claudia Laroye of The Travelling Mom visited Ypres with her family with In Flanders Fields – Ypres – the Menin Gate and Last Post

|